At the beginning of June, during one of the most stressful weekends of my life, I made a trip up to Dalston to meet two genuine heroes of mine. Matmos have been experimental electronica’s power couple for over twenty years, and have created a sizeable chunk of my favourite music of all time. They also have that other thing I love: albums you can geek out about, with reading lists, stories, technical experiments and an unsettling amount of flesh. Drew Daniel has an incredible metal-queering side project as The Soft Pink Truth, and is also a bona fide professor of literature. His partner M(artin) C. Schmidt is the one who looks more professorial. Although it appears to be slightly harder to dig up his side projects, he has been banging around a prepared piano and creates the videos for their live performances.

Later that night I’m going to listen to them soundtrack the pouring of buckets of glitter down a New York toilet and sewer system (“Shit into gold!” Martin yells gleefully at the end). The sonic descent is peerlessly intriguing, continuing to sink deeper and deeper for the length of the simultaneously boring and disgusting video. The set includes only one piece I recognise, despite owning all their records, a sprightly and chaotic romp through ‘Rainbow Flag’ from their expectation-upturning synth-only Supreme Balloon. Much of the rest of the gig is spent with the pair (assisted by a few friends) reacting to videos of Martin finding multiple improper ways of playing a piano. The sound is at times brutal and riotous, but feeling for the interplay between the different elements is inspiring and entrancing. The point when the on-screen Martin takes a break to check his phone for messages, and everybody on stage does the same, is genuinely and surprisingly surreal (see photo below).

That was the second performance of a two night residency at Cafe Oto; apparently we missed the dancier one the night before. I was kicking myself. But like I say, stressful weekend.

Anyway. An hour before the Sunday sound-check I caught up with the boys in the Cafe, and was charmed out of my skin. Two beautiful men, with the strongest rapport and capacity for finishing each other’s sentences I’ve ever seen in a pair of people. It becomes clearer through the course of the interview that there’s a strange mirror between their creative and personal lives. Their relationship has been going on as long as they’ve been making music together, and the two are inextricably linked. Every discussion of creative tension or inspiration seems to come with a tiny unspoken innuendo. Not a sexual one necessarily, just an implication that the romance and the recording are totally wrapped around each other.

Whatever it is, it makes them incredible interview subjects. And incredible musicians. As much as they put themselves down, and big each other up, it’s clear from the performance that they are tight, playful and brilliant.

Back to the interview. Before I’ve even sat down and started recording, they’re already at it. I probably check in to see if they enjoyed the show last night, and whether they’re looking forward to tonight. Whatever I said, by the time we’re recording, Drew is halfway through an answer.

Drew Daniel: It might be horrible, that’s part of the openness of trying to stay fresh and immediate. To avoid repeating these gestures that once had vitality because they happened in the context of improvisation, and then you start to cite them, and then this increasing artificality creeps in and you’ve sort of lost that directness. I don’t mean to stigmatise artificiality: sometimes it can be delicious.

M.C. Schmidt: We do very different things too. Like, kinds of things. I do more actual playing of the keyboard. So my answer to the same issue is that I somehow lose the ability to play. We play the song ‘Rainbow Flag’, and I know it’s in F, and it goes doo doo doo doo doo, and then on night seven I’m just umpph plflflflfhhh.

DD: Play it again!

MCS: I’m just not a musician. I just never learned discipline.

DD: What is the word again?

MCS: So where other people would lock in and get stronger and more robotic. I think I have a hard time not blaming that I sniffed a lot of glue as a teenager and it really ruined a lot of my memory. My ability to remember and repeat the way one should.

DD: That’s why I’m a sort of an external hard drive for Martin, where he’ll start a sentence, and it’s like a madlib, where I’ll provide the proper noun or name that is at the end of that sentence.

MCS: *giggles*

DD: For me the risk is different. I don’t have Martin’s chops, I don’t have his musical ability at all, but because I’m more oriented towards sequencing and rhythms I have to avoid the sort of control-freak, over-prepared problem with electronic music, where you can make it very blocky and press go and hear this content. But it’s musically inert, and audiences can sense that you don’t have a lot at stake.

MCS: I wonder, I don’t know. We’ve played with some people recently who, I know they’re just running a sequence, and the audience is just ‘yeaaaah, wooooo’ and I’m like ‘do you do this at home? When the record plays exactly the same sequence?’

DD: You think that’s valid though in the model of the tape concert or musique concrète though, so why is it not valid for the electronic music act?

MCS: Because it’s the social contract of the space where these things go on. If you’re seated, in a theatre, and the situation is a formal situation and there isn’t this unspoken contract that says ‘this will be a live show’, where people are standing in a social space like a rock club. There’s a stage, and blinking lights, and stuff like that. That’s a social contract that says ‘we will exchange energy’ (not to sound like some sort of weird new age thing), whereas the social contract of going to a symphony is not quite the same as that, or a film, which is even more like one of these concerts. There’s an implication that it’s going to be the same. We will sit and receive and we will appreciate and so on. But it’s a different thing, so I can’t help but feel that there’s some kind of weird lie being told, making people stand up and whatever… [trails off]

Alex Allsworth: Do you think you have a duty to expose that, and expose what you’re doing to the audience?

MCS: Otherwise what’s the point?

DD: We like to have it flow back and forth in terms of the raw and the cooked, with the pre-made video versus live camera-work, and I like moments of confusion about what the status of the content is. We very frequently have people think that the video was live when it wasn’t, and I like creating category mistakes. I think there are moments of lying that are interesting moments.

MCS: Well, it’s a technique to bring people in more, that sort of scratchy itch. If people are like: ‘what’s happening?’ and they’re trying to figure out what the relationship is, you win. You’ve already won.

DD: We have a sort of causality that is video as graphic score. So we’re interacting with the video in the sense that it’s giving us cues, like a sort of conductor. But we can also push back and avoid that or ignore it or disrupt it in various ways. It depends on the piece. There’s pieces that involve sync sound, but if you have too much sync sound then the concert turns into watching TV. It loses a lot of power.

I’ve been to gigs like that, one that springs to mind is Cornelius…

MCS: Cornelius! I was just about to say that.

Beautifully and perfectly in sync with the video, and the music is incredible…

DD: … and they get upstaged by those videos.

MCS: I wonder if we saw the same show, it was about five years ago.

Oh yeah. Of course, you were supporting!

DD: They’re amazing videos..

MCS: … but you just think, ‘those poor guys, what are you doing here?’

You look down and there are like three virtuoso guitarists…

MCS: … and they’re nailing it…

… and you don’t notice because you’re thinking about sugarcubes.

MCS: The Books were another thing where their thing was so tidy, and their films were so amazing, that you never looked down at them.

DD: So we like to have a push/pull. Martin makes videos that are deliberately designed to be interesting sometimes, and then boring. Where the flow will disappear and you won’t be aware of it any more. In part that’s from coming up at the rave era, it’s a technique to get people to shut the hell up if you’re not playing music that’s about dancing.

MCS: When we started, we were playing in…

DD: … chill out rooms…

MCS: … and not so great situations, and it was simply a technique to make people look over from the bar: ‘oh, there’s something happening there’. And all this stuff sort of feeds on itself. It’s also partly just because we’re perverts, but it’s why we ended up working with gross or sexy or…

DD: … gross and sexy…

MCS: … or abject sort of stuff because, well, if you put a picture of a cow uterus on a screen, people are going to look over: ‘Woah. What is that flesh that is being probed there!’ It’s a shitty showbiz technique. ‘Hey, look over here……… genitals!’

DD: To play in a really intimate space like [Dalston’s Cafe Oto] is a challenge for us of a new kind, because some of our show is engineered to counteract the black box rock club environment, and so when you’re here, where that’s not the context, you already have their attention. You have to scale back some of the gestures, because it’s so already intimate it would be obnoxious.

MCS: I felt kind of foolish pulling off some of our show last night. The most extreme example was about two years ago. Frequently we don’t know where we’re going to play, or we just get a piece of paper that just says ‘Belfast Music Academy’ or something like that. We had a show that was very rock, a drummer and guitar player, we showed up at Belfast University and it was like a 48-channel musique concrète acoustic Deathstar of technology.

Literally, the audience sits on a grid so there are speakers all the way underneath them, as well as a ring around them, and another ring over their heads.

DD: And our set was so inappropriate.

MCS: We’d come with this stupid rock and roll thing.

And you could have quite easily adapted to play that environment.

MCS: We would have LOVED to have done that.

The machine that is the music industry in a way doesn’t care what you are. ‘You’re a band’. Frequently we show up and sound guys are like: ‘so you’re DJs?’ ‘Well, no, we have a drummer, and we have all this elaborate shit,’ and they’re like ‘Oh…ohhhh’ [that second oh sounds exactly like a sound tech’s heart breaking]. They read the word electronic and they stop thinking. And I don’t blame them. I understand. I’ve had a job before.

DD: And it’s weird that the word laptop, it gets used as if it was a genre. You don’t say ‘all fine artists… well, they use brushes. Another brushes person’. Goya, Velásquez, Francis Bacon, it’s all just brushes, basically. But laptop is supposed to connote a style or genre, and I don’t know. I use laptops, Martin uses a laptop to roll the video, but I always thought we were the band that brought too much shit.

MCS: Witness our beige castle *gestures across room at canvas covered tank-sized block of music equipment*

DD: So when Martin plays the flute, people literally laugh at just the idea of ‘and now I’m playing the flute’. It’s like the jazz flute moment in Anchorman.

MCS: Only I’m not that good.

DD: It’s okay, he isn’t either. It’s just flute-sync.

[At this point Martin leaves briefly to get a coffee]

DD: Now you can ask me about The Soft Pink Truth while Martin’s away [After the previous night’s Matmos show, Drew went straight to Vogue Fabrics to play a set as his electro-house alter-ego, The Soft Pink Truth].

*Excitedly* OH YEAH, how was The Soft Pink Truth gig last night?

DD: Oh, it was so much fun.

First time in ten years?

DD: Yeah. I was really nervous about doing it, because I’d had no chance to sound-check and no chance to practice, other than singing along to the backing tracks in my hotel room and in the van on the drive to London. But it was super fun and exactly the way I like to present The Soft Pink Truth, in a small, sweaty, dingy bar, and it’s a basement, and everybody’s like this close and I just blast the beats and check my vocal and go for it. I become like a very preposterous macho hardcore band frontman, where I’m just singing, and put my arm around people, and singing and getting in people’s faces and like, ‘who’s with me, are you with me? We are together, let’s do this!’ [For this bit Drew actually jumps up, puts his arm around my shoulder, and shouts into my face. It’s pretty inspiring.] Fully acting out the fantasy of being a frontman. It’s ridiculous music. I don’t know if I’ve heard any of the tracks.

I’ve heard one of the tracks so far. [Ready to Fuck]

DD: The record that I’ve done is all covers of classic black metal tracks. Burzum, Darkthrone, Venom, Sarcofago, Hellhammer. So last night I did Mayhem and Darkthrone and Venom in this gay bar with everyone listening to RnB.

How did that fit in?

DD: Oh, not at all, but it was totally fine. You should probably ask some of the people in the audience what it was actually.

So it was a weird night. Whenever you do two things in one night it’s weird. But I sort of like the manic energy that that requires.

We just had a show with Oneohtrix Point Never in New York, and afterwards we DJed with Björk and Oneohtrix in a heavy metal bar. So it seems like bringing dance music and metal together is what I’m into at the moment. Last night was playing metal songs in a dance club, and last week with Björk was like a metal night where we show up and play dance music.

I guess I like the putting the chocolate with the peanut butter approach. Like putting worlds together that don’t go and forcing the issue of ‘why not?’ And usually the answer is that people are way more open to things than you think. There’s so much fear and condescension about music scene identity stuff. Assumptions that people are less open than they often wind up being. There’s this fear of getting bashed and mistreated that makes people understandably want to protect themselves. But I think if you’re more open-hearted and you don’t assume from the get-go that people won’t understand or won’t accept you, then it works out. You have to believe in yourself. It’s a great quote from Kim Gordon, who said ‘people will pay to watch someone believe in themselves on stage’, and I think if I had been doubtful about my own shit in that bar then it wouldn’t have worked. If I’d been like indie Cindy ‘I hope you guys like this’, but you can’t… let them see… that you’re afraid! Just be like, ‘you, me, here, we can do this’.

MCS [who has returned, obviously]: I mean, it was an actual movement for a while there. To go to shows where people were just, ‘I’m sorry’.

DD: I remember people patting Cat Power on the back when she would play in San Francisco, it was intense. She’s got nothing to be afraid of. I don’t know. I’m biased about The Soft Pink Truth so you should ask him how it went?

*eyebrows at Martin* Did you enjoy it?

MCS: I don’t know, it was good fun? I have an impossible time separating that sort of thing from the technical situation.

So are you involved in any way?

MCS: No, so we have a weird kind of boyfriend thing with this band, because he literally started it because… he sort of loves dance music and will move things towards that and I’m the one who pushes back.

DD: Martin likes to free improvise and stuff like that.

MCS: It’s not that I don’t like that. It’s just that… Drew’s a powerful personality and we would be a techno band if it weren’t for me, because people like that, people respond to that, he’s really good at it. We could do nothing but that. So this is where The Soft Pink Truth came from, I was just like, ‘Why don’t you make your own fucking record instead of trying to make me do these techno things all the time?’

DD: I think it’s healthier for Matmos because Matmos can be about the poetics of sounds sources. And it can be a really open project as far as genre, where we don’t have a home in any genre. That’s intentionally how we like it, to be sort of nomadic with respect to whether it’s medieval and folk instruments, or disco, or fake doom metal, or just tape cut-up. I like the feeling that I just have no idea what the next Matmos album is going to sound like. We obviously have our fingerprints and our styles that we love to fetishise, but I genuinely like the lack of responsibility to a ‘scene’. I think it’s part of why we’re still at it after 21 years. For a lot of people who were our peers everything was about a particular dancefloor scene and that mutates so fast, and the turnover of who’s compelling is just so cruel. Capitalism needs something new to sell you every couple of months. I think in a way, because we have this itinerant attitude, we’re still here.

[At this point the tape cuts out, running out of battery. It’s absolutely infuriating, as it’s probably my favourite bit of the conversation, but by the time we’ve cut back in, I’ve accidentally started sounding like I’m slagging off their authorial process.

Basically, the point I make is that the common thread that holds together throughout the history of Matmos is that tension between the dance and the exploration. These kind of wild rambling improvisational soundscapes that occasionally bubble into exhilarating dance rhythms. The push and pull can be heard throughout their albums, where a drifting moment will suddenly have a breakbeat burst out of nowhere. It’s what I love, so I tell them this. We talk about ‘the feral’ as one of the places they like to keep the music. We discuss how it sounds like this tension in the music seems to represent a certain tension between them. Or at least that’s one way of understanding it. The push/pull between Drew’s dance and Martin’s experimental noise work locates Matmos in a very particular place, that’s actually almost exactly where I locate my own musical tastes. Hence they’re my heroes.

This is briefly the bit of the interview where I start saying interesting things and almost sounding professional. We can draw no conclusions from the fact that this is the section I have no evidence for.

I spot that the recorder is out of battery and, as I fumble, I think I must dissemble about how bad I am as an interviewer, and how great they are as subjects. Drew mentions that in interviews he’s at no risk of becoming a stereotypical rock band, with monosyllabic responses to questions. That’s where we return, and I start being even more awkward and bumbling.]

MCS: Yeah, so you ask a really long complicated question and they’re just like ‘Yeah’.

But you’ve got a bit of a cop out here in that there’s always some kind of elaborate theory behind the music. Is that a cop out? Sorry. I wanted to ask this, but I meant to frame it in a much less hostile way.

MCS: No, no, it’s fine. What do you mean though, so is the theory getting in the way of the music speaking for itself?

So I love reading up about this stuff, looking up the liner notes, searching online and being ‘oh wow, that’s a cow’s vagina’ and linking that back to Valerie Solanas and reading the SCUM manifesto. But is that like a PR thing, so that people have something to talk about?

MCS: It certainly did not start as a cynical plan, but it did work out conveniently! We were just doing that to… keep ourselves amused.

One of my other versions of the question (still hostile) was just: ‘Are you just easily bored?’

DD: No, I think it’s just, for me, thinking back to the records that really moved and inspired me. Reading the liner notes to Coil’s Scatology while listening to it at the age of 16, and there’d be not just a lyric sheet but there’d be a reference to medical facts about treatment of the clap, or quotes from Lautréamont, or a reference to the Manson Muders, or an account of the divine myth of Danaë and the shower of gold. Reading this in Kentucky, where everyone else is listening to straight-edge hardcore bands and here’s this strange onslaught of subculture and sexuality and history and mythology and literature, I just felt that what a record can be, as a field of sounds and signs and information all moving like a solar system around each other, is so inspiring and so appealing that I just wanted our work, my own work, to involve the same co-ordination. Here’s the music, here are the ideas, here’s a source in the world that has to do with history, or that has to do with sex or has to do with the past.

MCS: But to answer the question from the other way, I sincerely hope that the music is listenable knowing nothing.

DD: Yeah. The terrible drawback is that reviews and responses to our work often become these regurgitated descriptions of our methodology, rather than someone giving themselves the space to critically evaluate it and say, ‘I like this, I don’t like that, this made me feel this, this made me feel that’. I read very few reponses to our work like that because everybody’s so busy going ‘oh my god, they aimed these lasers and there were these snails,’ and it’s cool that they want to relay that information…

… but it means that every review becomes the same.

MCS: Well that last album we made…

DD: … The Marriage of True Minds… [I nominated this as album of the year last year, incidentally, and stand by it]

MCS: … was so goddamn elaborate.

And it was gorgeous. And stands totally coherently without any of the theory. I feel like it’s worryingly ‘accessible’. It’s the album I can finally persuade my friends to listen to.

MCS: Other people have said that. I had no idea that was what we were doing when we did it.

DD: There were a lot of moments of doubt with that, ‘have we been consistent to this concept enough?’ Martin is really the cop about ‘you’re not sticking to the concept you said you were going to do.’

MCS: Well it was his idea in the first place, so there’s a question of ‘what are we doing here if you’re not sticking to your original intention?’

DD: He stops me from cutting corners, and bless him for that. There’s a lot of fights about it. But at the end of the day all of that should drop away. People should just be able to experience the art and intuitively respond, but I think in a weird way our concepts work too well; where the album becomes a means to disseminate the meme, which is its concept. So it could be interesting for us if we made a highly conceptually, truly focused record, but simply didn’t reveal what it was.

Lock it in a box.

DD: Yeah, and maintain a sort of strategic silence where we just don’t reveal that. I tried to do that a little bit with this one by not revealing the concept that I was transmitting in all of those psychic sessions. That was an attempt to have a kind of secret.

So there really was a thing? There was a specific entity you were thinking of?

[For those following at home, I should probably clarify here. The Marriage of True Minds is an album about ESP, and the bulk of the tracks are the result of ‘scores’ generated from transcripts of hundreds of ‘Ganzfeld experiments’ conducted by the couple. In these experiments a subject is put into a state of sensory deprivation (white noise, red light, goggles etc.), while a tester in a neighbouring room attempts to transmit a specific message by focussing on the thought. Matmos have only ever stated that they were trying to transmit “the concept of the new Matmos album.”]

DD: Oh yeah. Definitely. There really was. There was one thing that I was thinking.

MCS: He won’t tell me.

DD: I haven’t told anyone.

Because it’s always presented as just “the concept of the new Matmos album,” I was worried it was just a recursive thing, of thinking about the concept of getting people into a room and thinking at them about the concept of getting them into a room…

DD: *laughs* You see now it’s going to work on you.

I mean it could be that we’re living in a world that is increasingly dominated by language and signs at the expense of the sonic. And that the sonic is like an immanent physical experience, that’s not necessarily linguistic or not necessarily cultural. It’s something that we have to capture with signs and ideas. That we have to put tags on. In the way that, literally in Soundcloud, you have to put tags on sounds and say ‘here’s what this song is for/about, here’s who this song is for’. And that’s a beautiful system, it’s not like I’m against language, I’m a literature professor. But you have to see that there’s a sense in which we’re avoiding dealing with sound on its own terms, and that’s what I call the queerness of sound. The sonic has an immanent queerness, in that it resists signs and categorisation. And maybe, my dream for Matmos, if I could shut up, would be to let the sonic become, as you say, ‘feral’, and really become prior to all this theorisation and conceptual wrangling.

MCS: It was sort of what I was after with Supreme Balloon, honestly, where the rule is just ‘no microphones’.

And was that also a callback to the back of Queen’s A Night at the Opera, with its bold linker note proclamation ‘Still No Synthesisers’ and replacing it with ‘Pure Synthesisers’.

MCS: You got it!

DD: Bless them.

MCS: Bless them who, three records later, were half-synthesiser.

But to hijack this interview to start talking about my relationship with Queen, which is probably not something I’m supposed to do, I remember listening to ‘The Prophet’s Song’ and realising for the first time that music was recorded in a studio. I remember, very young, thinking ‘wow, they’re not just people, in this record’. They’ve spent time laying over vocals, recording and shifting things over itself.

MCS: That makes perfect sense. I think it was something with Holger Czukay, it must have been written on the record because I’m not a big interview reader, where he said “The studio is my musical instrument.” Like ‘I’m not really a bass player’. And he was kind of doing the work, although I didn’t know it at the time, of explaining what musique concrète was, to a rock audience. The idea that he studied with Stockhausen and all that stuff was ‘of course’ to him, and from an academic standpoint.

DD: I feel like my introduction to musique concrète was actually the Halloween Sound Effects records that I had as a small child, because they were isolated tracks that were just chains clanking, and lightning strikes and then woman screams. I had this seven inch of just haunted house sounds that I loved. And of course it was about this schlocky mood of horror, but if you pick up from another handle it’s also saying that the sound of the dog as itself, or the sound of chains is already compelling audio. It’s an experience. I’ve never really thought of it before but now that I think about in a weird way there is a sort of connection. The Musique Concrète tradition is all about these Estudo Objets and studies of a particular object, but in a way Halloween records are already doing that.

And there’s a serial thing, isn’t there. There’s not a narrative structure to a sound effect record, just a series of isolated sounds, that happen to have been sequenced together.

DD: I remember one was a woman screaming and then this weird male voice saying “I am an expert in the art of flogging.”

*sniggers all around the table*

I used to giggle so much at that.

So you do feel that there’s a tension between the concept and the music and the language? To make this about me again…

DD: … no go on then…

… I have to write about music, and I kind of hate it because I just don’t think it’s possible, but at the same time I love music, and so I want to talk about and get across to people what I love about music. How do you talk about music? How do you talk about music with each other when you’re trying to explain an idea or a concept or whatever?

DD: How do you stop, is really the rejoinder here. You can think about it in terms of ‘who is this for and what are we trying to do here?’ And that can be about genre, and locating yourself on a sort of map of known genres, or trying to secretly build a tunnel between this genre and this genre over here, or you can think about what’s missing. What do we have, and then what’s not here. And is the fact that it’s not there a good thing? Because it’s also about the absences within the music. The gaps and the voids. We have a friend Jay Lesser, who when he’s working on tracks will look at a spectral analysis of the frequencies and see where the gaps are. I’m all about in this register and this register and not over here. So speaking about music it’s always about a dialectic between what has been erased, avoided, suppressed.

It’s also a temporal experience of testing whether you have something valid that’s new, or whether this is secretly you recreating something you already did. There’s a comfort in that, but how to avoid that comfort? That’s one of the challenges, especially the longer you’ve been at something. If you have a substantial body of work behind you, for better or worse…

MCS: Are you answering the question?

DD: No. I thought about this a lot writing the Throbbing Gristle book. Talking about Throbbing Gristle was a real challenge for me because I don’t have any conservatory training, and I can’t talk about notes and chords, but of course their music is largely about processing and I don’t think we have a rich timbral language for the description of signal processing. We have very basic, rough versus smooth, wet versus dry, axes of comparison. So the language is really impoverished to talk about a lot of the things that are most interesting about that sort of music-making.

And then there’s the implied social world. I think every piece of music implies some way of being in the world and some model of either community or refusal of community. So when you think about music you’re also thinking about its openness or its restrictiveness, its gendering or its political vision. The utopian collectivity of free improvisation versus the singularity of the audio tyrant in their bedroom that controls everything. There’s always a vision of a way of relating to others, that you can talk about when you’re talking about music.

MCS: I think they meant when you talk to me.

DD: *laughs*

MCS: And then, forty minutes later…

It’s alright. It’s all good stuff. You’re answering a question that was better than my one anyway.

DD: So when we are working together?

If you have the spark of an idea, or you have the spark of an idea [indicating each of them in turn]… what do you do with it?

DD: Well I’m always forcing these things I’ve just made on Martin, with these eyes filled with expectation: “I hope you love this.”

MCS: It’s more of a threat. It’s more like: ‘you’d better love this.’

DD: *chuckles*

MCS: He makes a lot of stuff by himself, that he then presents to me. And certainly, in terms of our albums, there are things he makes that are just ‘those are done, you don’t need me,’ but then some things really sorely need a lot of work. I mean, rather than talk about it you just sort of ‘do’. Do the thing.

DD: I’ll come in on Martin playing something and just be: “oh my god, that’s amazing, we should record that.” Martin likes to play. Play an instrument, play an object. I’m much more likely to go, “let’s record this.” I’m more oriented towards making records, and Martin’s more oriented towards just picking up something and making sound for the sake of doing that. Martin’s purer.

MCS: Well, I will make recordings of things. It’s just that we have different technical methods too. He works with Ableton, so increasingly it’s just like twenty minutes later and he has a thirty track orchestrated thing, that’s already got compression and effects and it’s all pooping out of that hole in the side of the laptop.

DD: Martin’s a much better engineer than I am though. Even though I’m more likely to say “oh let’s record that”, as far as miking an object and listening carefully and where’s the right place to put a microphone and what about this room or situation could I use well, Martin’s much better. There’s a lot of push/pull about ‘let’s record it, you put the mics up,’ because I don’t want to make a bad recording and I’m just less reliable. It’s like how we move through museums. I move really fast, Martin looks at everything really slowly and carefully.

So do you just go round three times while you’re waiting?

DD: Kinda. Or just, “I’ll meet you at the gift shop.”

MCS: And then half an hour later, I can’t remember anything and he remembers everything.

So how far through are you on brainstorming whatever’s going to be the next Matmos album?

MCS: Not at all. Not anywhere.

DD: It’s his job.

Do you get to a point where it’s just, ‘oh, we haven’t done a Matmos album for a few years…’

MCS: It’s weighing on me already, how long it’s been.

Oh god no!

DD: Well, we spent four years on Marriage of True Minds, which was too long, we didn’t need to spend that long but it’s because the academic life that I’m leading has a certain rhythm to it and you have to work very hard if you’re going to do it at a serious level. So it wasn’t as if we got out of bed and made a cup of coffee and worked on that album all day every day for four years, Jesus Christ…

MCS: No. We’d have forty albums if we did.

DD: That’d be a nightmare. But I feel like we’ve made some pieces based on Martin’s videos that we’re touring on this tour.

MCS: We could make an album out of what we’ve got here. But will we?

DD: Well that’s really up to you.

MCS: We have this backlog of shit we’re supposed to do. We were supposed to do this version of Robert Ashley’s ‘The Backyard’ that we’ve done live many, many times.

DD: So we’d like to record that. There’s a Terry Riley piece manipulated into our own kind of free remix that we did with Kronos Quartet, and it would be great to record that. There’s a lot of music that has not made it onto a recording. But really, because we take turns, and Marriage of True Minds was my idea, it’s really up to Martin what we need to do next.

We’ve also both done solo records this year. My solo record comes out in two weeks [it’s actually already out, because it’s taken ages for me to get this transcribed. There’s a review here, but the short version is ‘fucking brilliant’]. Martin’s done a solo record of prepared piano. It’s really beautiful.

MCS: It’s REALLY beautiful.

DD: I can say that, you can’t say that. It’s kind of like this asian, chinoiserie exotica, a fantasy of the orient that plays with…

MCS: That sounds so much more interesting than the idea.

Well that’s words, isn’t it!

DD: It sort of courts these crypto-racist exotica ideas of foreign music, but I think it does it in a really sort of psychedelic and organic way. I think it’s really good. I can say that, if you said it would be gross.

MCS: It’s reeaallly goood.

And is that just you playing? Is it just ‘conventionally’ prepared? Are there several layers?

MCS: It’s pretty straight John Cage, coins and bolts, bits of rubber. And then there’s electronic stuff. I did a tour last year with Mark Hosler from Negativland and my buddies Wobbly and Thomas Dimuzio. We did a whole quad improv tour of obscure venues in the Eastern United States, and there’s some recordings of that folded into it. There’s a whole cut up piece that I made twenty years ago that’s part of it, with a short story read in Chinese. I asked a friend of mine to write a short story, and then I asked another pal of mine to translate it into Chinese and read it, and I no longer remember what the story is about, it’s been so long.

DD: I thought it was about breaking into someone’s house.

MCS: I think it’s sort of a pervy story about what seems like a child molester is in a child’s room and about to touch them, and it’s sort of revealed that it’s just his father.

DD: And as we know, that must mean there’s nothing perverted there.

MCS: And by the way of describing this scene, these banal gentle things, they look dark and perverted, but you know…

But you couldn’t just have that as a story, you had to put it into Chinese.

DD: When it’s sold in China, it’s going to explode.

MCS: I do seriously wonder. Because I don’t know what it is, I cut it off at some point ten years ago, and I don’t even know if it ever resolved. And I don’t know, in Baltimore I don’t know any Chinese speakers…

[Drew interjects with suggestions of people they know who can do it, proving Martin’s memory defaults and Drew’s status as external memory, but its probably not interesting enough for transcription…]

DD: Anyway, we both make solo records, and I think that sort of delays the new Matmos, because both our solo records are sort of indicative of the sort of yin yang thing we’ve got going on here.

MCS: Disco covers of black metal songs, and prepared piano!

DD: It’s a wonder we can even find a place in the middle to meet. I think sometimes couples are weird in that there’s a centrifugal force where you blur, and become this third mind, this average of the two.

And is that part of the story of The Marriage of True Minds?

DD: Definitely. The sort of intuitive fusions that occur. When you’re two people together for decades on end, then the sort of things that the other person doesn’t like, you stop doing, because it’s better to go towards the things on that shared island, but also as you get older you get crankier and you start to like less things and that’s the dark side of the couple, is this sort of shrinking island, losing territory. But the opposite of the sort of centrifugal thing is the centripetal, like, ‘I wanna be the opposite’. People just looking at us, sartorially, we don’t look like we belong together. In most elevators in hotels there’s this ‘why are YOU two getting on together?’

MCS: One time in Kentucky, we were getting arrested. Well, I wasn’t getting arrested. Drew peed on a tree…

DD: … and a cop arrested me for indecent exposure…

MCS: … and a cop appears out of nowhere…

DD: … I mean I wouldn’t have been peeing if I knew there was a cop there…

MCS: … in the middle of this park and he’s just like: “Put your hands on your head or I’m going to blow your head off right now.” And we hadn’t even seen the guy a moment ago, and we’re both like *childish yelps of panic* in the middle of this park. And he starts interacting with Drew and he looks at me and he just says, “You can go.” And I was like, “I’m WITH him.” And he was just like, *uncomprehending grunt*.

DD: Because we just don’t scan. A lot of gay couples do that, like, ‘matchy matchy’ thing where they get the same shoes and the same glasses.

MCS: We are the absolute opposite of that.

DD: We just don’t want to do that…

MCS: … that partner look thing.

I think that’s right though. It brings people together better if they’re different.

MCS: And it’s just creepy, it kind of freaks me out.

DD: Well now, it’s fine if you’re Gilbert & George, but if you’re not then, well, just don’t.

MCS: Yeah, but they’re worth it in a different way. But they’re creepy gentlemen, actually, but I think they’re well aware of it, you know.

DD: Yeah, they own their creepiness. They’re not suppressing it. Anyway, we have our sound check in about nine minutes, do you have a final question?

Oh god, that’s no time. I promised Kier I’d try and get something better than that Butt Magazine interview where you ended up talking wistfully about the patriarchal semiotics of the gay fisting scene, and I just don’t know if I can jump to that in nine minutes.

MCS: Well you should know, that interview took four hours. We did a two hour interview with them, and then he looked at his thing and none of it had been recorded. And he was just, can we do it again?

DD: And it was hilarious, because we’d gone in so many different directions, it wasn’t the same interview by any means, but it was kind of like, what the fuck.

I guess I’ll just have to be really boring. What was the actual process for the Marriage of True Minds? It says using the transcript as a kind of score, but what does that look like? Was every track done in the same way?

MCS: We wanted it to all be the same. That was the idea. That each of them would be based on listening to the transcript of each psychic session. But really there’s only a few.

DD: ‘Aetheric Vehicle’, ‘Mental Radio’ and ‘Ross Transcript’ were very precisely single transcript, single song, and the shape is a very A to B to C to D to E transcription with a sort of rebus-like logic. Whereas in ‘Very Large Green Triangles’ the musical form from beginning to end is not a reflection of the progressive ideas of Ed’s thing[Ed Schrader of Ed Schrader’s Music Beat (coincidentally we have an interview with them coming very soon too)], it was much more that I wanted to make a Baltimore club pop song with Ed’s vocal idea as the sort of riff at the centre. That one was not at all faithful.

MCS: We use these conceptual restriction things. We fully intend to absolutely hold to the idea, while at the same time being perfectly aware that we will do whatever want, using those ideas as a jumping off place. I think he went too far with the finished product. There was a bunch of stuff that he made, kind of without me. We had trouble there, about three years ago.

DD: Like ‘Tunnel’.

MCS: And he was like: “these are done.” And I said, “A) they’re not done because I barely play on any of them; and B) they’re just songs, they barely have anything to do with this concept that you had.” And so we kind of started again.

DD: It’s part of why it took so long. It was a real crisis for me because I thought we were further along than Martin thought that we were, and because it’s a sort of co-tyranny where we each have veto power, we had to fight it out, about what’s the state of this album. And what is psychic enough? And it became apparent with so many people seeing this triangle image in the Ganzfeld Sessions that we did…

MCS: … that we couldn’t summarise the idea that so many people saw a triangle. So we took all the parts where people saw a triangle…

DD: … and that’s why ‘In Search of a Lost Faculty’ exists. To document that collective experience, which if you privatised it as ‘one session equals one song’ you could never really get that sense of a community coming together.

MCS: *sneering gently* Community. You are an academic.

DD: The biggest stretch is those covers. Those covers are purely an attempt to bookend the project with musical reflections on the appeal and the allure of telepathy, the romance of telepathy. Or telapathy itself as a figure for amorous connection. That’s pretty fucking loose. That’s not conceptually tight with the sessions, it’s just my decision. I really wanted to start with that Holger Hiller track, and that Buzzcocks track because to me, that explains why we care about telepathy, the emotional appeal and allure of this premise, to situate it in an emotional way. Which isn’t all that conceptual, frankly. It’s more of a core intuition about why we spent years bothering with this stuff. So, it’s sort of a supplement to the premise?

MCS: Yeah, I mean the truth is that we’re crappy conceptual artists. We don’t hold to the…

DD: … we’re not strict…

MCS: … at the end of the day. I mean, I’ve said this before in other interviews, I can just feel these words coming out of my mouth. At the end of the day we make records that we know people will want to listen to and enjoy listening to so we will just throw the fucking concept out in order to make something that it seems like people would like. Not so much that we would abandon it utterly, but… yeah…

DD: You want to find a concept that is tight enough to be resonant and suggestive to people but the more you look at it the more it stops being a singularity of a single thing, telepathy, and becomes the network of relations between objects and actors and agents and people and material things and environments and economies. And the singular just starts to sort of, web out into the world, and that’s the part of working in this way that I really love, it’s not this sort of visionary ‘aha’ of ‘I see the whole record’. I think I almost never have had that. I think the only time was when we came up with the names and concepts for The Rose has Teeth…, that was very much a conceptualised in advance record. But aside from that one it’s usually a sort of, ‘I think there’s something about medicine that I want to think about’ or ‘there’s something about telepathy that could really go somewhere’.

And that’s really apparent in The Civil War, where it’s quite clear that ‘this is about arguments’, ranging from highly personal mental breakdowns to all the different kind of forms of breaking apart, from the state down.

DD: Yeah, The Civil War, we had some nasty arguments about it.

MCS: Wait, were you just describing The Civil War?

DD: We were just saying it has all these levels of tension.

MCS: Yeah, but it was never conceptualised beforehand, that’s just you reading it there.

DD: But you saw it was Valentine’s Day and you were like, “I think our record is called The Civil War.”

Because it feels really coherent.

MCS: Yeah, it’s good right?

DD: That’s a Martin record.

MCS: And honestly, it was started and it was going to only be piano, and it just didn’t work, and we couldn’t get it, and along the way to trying to make this piano record we had these things that ended up being about wooden boxes and strings and guitars and the hurdy-gurdy. The piano album was going to be called ‘The Coffin of Music’.

DD: Which is a Joyce poem…

MCS: … describing a piano. The coffin of music.

DD: But it never happened, and instead The Civil War happened.

MCS: Yeah, the only piece from the piano album that ended up released was on The Rose Has Teeth… was the William S. Burroughs track, the piano rag at the beginning.

DD: We had a piece from that album where Martin had strung dental floss through the piano and we made beats and rhythms out of that, and we sent it to Björk and we were like, ‘Oh Björk, will you sing on this?’ and Björk at the time was working on… was it Medulla?

MCS: The all singing one? Is that Medulla? Yeah.

DD: Yeah. And so she ended up writing her song, ‘Mouth’s Cradle’, originally written to go with our dental floss song…

MCS: … and then she was like, “can I just keep this song?” And we were *resignedly*, ‘uh, okay’.

DD: So she didn’t use any of that music, but she put that melody along to our thing. And so basically this piano album that could have been and wasn’t, we got The Civil War out of it, Björk got her song ‘Mouth’s Cradle’ out of it. So I feel like everybody got something cool, it just went in some other directions.

So now it exists just as a sort of score for all these various pieces.

MCS: I really wish I could remember what that song actually sounded like.

DD: It’s funny in a way that now you’ve made your prepared piano record, because it’s like your piano record…

MCS: … yeah, I had to do it myself…

DD: … was like ten years in the birthing process. But it finally arrived.

MCS: Whatever. There’ll be another one along in a minute, too.

DD: And on that note, we should set up.

Words: Alex Allsworth

Headline photo: AJ Farkas

Live photo from Cafe Oto: Dawid Laskowski

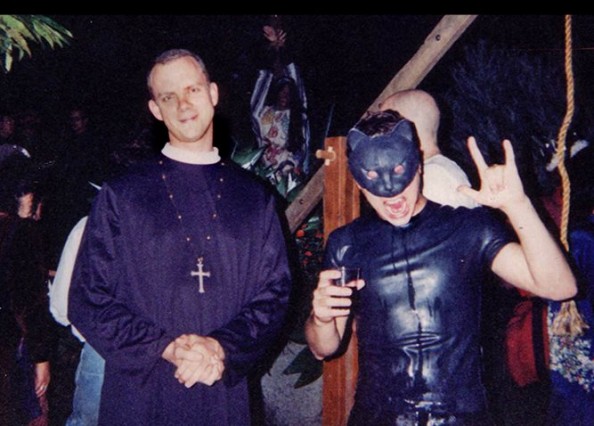

Halloween photo: Posted on Matmos’ Facebook page in 2012 to celebrate their 20th anniversary as a band and a couple

Follow us

Follow us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter Follow us on Google+ Subscribe our newsletter Add us to your feeds