Ah, sweet Twitter debates. Nothing says ‘worthy opinion’ like 140 words being reported by every music magazine and blog in the Western world. We’re in scary new times, or at least have been for about fifteen years. Music caught the wave of internet-led unemployment super early, around the beginning of the century, and it hasn’t so much fought forward with plans to improve the state of the industry as simply waited around for everyone else to feel the same pain so we can all wallow in it together. And we all know how those ‘we’re all in this together’ theories work out…

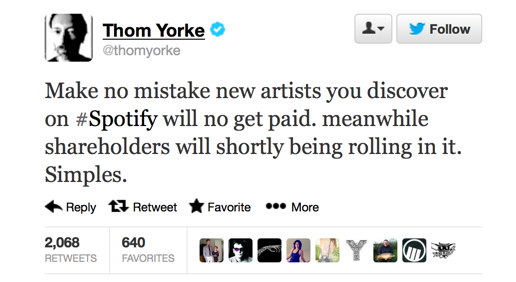

As you may have noticed, Nigel Godrich and Thom Yorke took to Twitter on Sunday to announce that their post-Radiohead work (essentially anything not on EMI) would be pulled from internet streaming service Spotify, claiming it wasn’t because they weren’t benefiting, but because new artists weren’t benefiting, and of course everyone knows Radiohead only employ business strategies which assist new artists.

Erm.

Since In Rainbows, music fans around the world have held Radiohead aloft as the moral compass of the indie world. It’s like starting off as a mediocre Britpop band and spending over ten years getting famous thanks to EMI’s insane 90s marketing budgets is the sure fire road to credibility. Using that decade-built mainstream fan base to employ a ‘pay-what-you-want’ strategy in the internet era, while your old label burns behind you (finally to disappear up the arse crack of the City of London), makes you mega, mega credible.

That’s more of a personal gripe though, and of course all artists, whether they’ve gone the route of the major or the indie, deserve a say in how their music is used and the opportunity to work out the best way to benefit from it. Most artists on majors won’t speak out about Spotify largely due to the fact that majors have such a high stake in the project, so it was always likely that any ‘whistle blowers’ were going to come from the outskirts of the industry even if once they were firmly in thrall to it.

Foals’ Yannis Philippakis decided to add to the debate. Never a man of few words, he wrote: “Arriving at the eleventh hour but Spotify should be legally obliged to pay artists a respectable royalty” and then went on to dispel the much circulated rumour that ‘it’s all about the live shows nowadays’ in true sarcastic fashion: “Yeah that’s right all the bands playing Doncaster Leopard or whatever getting a sweet 75k”.

To another frontman whose opinion is always entertaining, Hookworms’ MJ. In an NME blog post he argued,

“I’d be the first to agree that the old industry model is flawed, but no more so than this new one. We need to look to different approaches such as drip.fm, where you are able to subscribe on a much smaller scale to a record label like Domino or Captured Tracks. This way, many of the middle men employed in the music industry aren’t taking such a cut and both the labels and artists benefit.”

Throughout this debate it always seems people’s hatred is aimed at the middle men. Much like the public political consensus seems to be that everyone hates civil servants (or just doesn’t understand what they do), everyone hates the graphs and budgets men and women of the music industry. According to this argument they’re the people who mean artists get small royalties, the people who keep themselves in work while artists suffer.

I’ve got friends who have been desperately trying to enter the world of work via labels and promotion companies. Turns out there isn’t that much work around. Labels are tightening their belts, and that means losing a bit of weight around the old workforce waistline. Artists routinely complain about middle men despite the fact that it’s the middle men who help the labels exist – if their issue is with the middle men then their issue often lies with the idea of labels existing at all. Here though, the big middle men companies have more competitive gain over independents when it comes to online services.

Then there’s the estimated $0.00966947678815 fee-per-play stat which people roll out when criticizing streaming services. Of course the situation is a lot more complex than that. Big labels have distribution deals and take big cuts of income from the likes of Spotify, and that money eventually flows down to the artist; but, like all revenue which meanders through the big players, the actual artists are going to end up with a relatively small proportion of what was initially handed over by the services. It’s much harder for independent artists to compete at this level, and their distribution won’t be as big so their cuts of Spotify revenue won’t seem so fair.

Spotify and its ilk are still a work in progress. The idea initially was that if everyone paid £10 a month to use it, worldwide, you’d suddenly have a massive revenue income. And, with subscriber numbers rising, it does seem to be heading in the direction they were hoping for, even if at a snail’s pace.

The argument that royalty fees should be fair, businesses should be run in order to benefit the musician and labels shouldn’t squander money unnecessarily are all good points, and should all be looked at. But Spotify isn’t the first business which should be criticized for damaging artists, and seeing as anyone can at least get their music up there hoping that it could, at some point, be found by new audiences, it does more for new music than the real demons of the industry.

Is this rallying against Spotify more of a fashion statement than a moral one? If artists are going to start getting on their high horse about how the way their music is sold ties into benefits for new artists, shouldn’t they be tackling all the issues surrounding the music business?

Here are three more seriously ill moral practices blighting the music industry at the moment…

1) Supermarkets

They have been routinely attacked for their stance on paying producers of everything from tea bags to wine. Most of you will still remember the days when CDs were £15 (I can, just about), overpriced by the industry in line with the aggressive marketing of the format. They claimed you could eat your dinner off of them and they’d still play. As many people eventually worked out, the format wasn’t that strong, and paying £15 for something that costs about £1.50 to make (if you’re using scale of economy) doesn’t seem that reasonable. Fast forward to the past couple of years and the supermarket prices haven’t so much done a U-Turn and as gone so far in the other direction they’re on the fucking moon.

In Graham Jones’ book on the death of record stores, ‘Last Shop Standing’, he recounts a story from Pendulum Records in Melton Mowbray. Independent record stores were being sold the Coldplay album ‘Viva La Vida’ it by the label for £8.95, for the shop to sell it at £10.99. That’s not a massive mark up when you consider just how many CDs you’d need to sell to cover shop overheads. Soon enough the shop found out that Morrisons was selling it for £6.99. Pendulum was then put in the mad position of buying the album from the supermarket chain instead of from the supplier, just to compete.

Now there’s something obviously wrong here. Either the supermarkets are cutting costs of the CD to bring in customers who like Coldplay but wouldn’t necessarily like Morrisons, or they’re being sold the CD at a cheaper price than the indies are because the label are too scared of the size of the supermarkets to battle against them and ask for a fair price on their stock.

The winners: Supermarkets, who get loads of new customers.

The losers: Labels, who receive less money for their product, therefore cutting their budgets while other stores get an unfair deal – stores which would normally be the first retailers to support new talent.

The next tweet I’d like to see from Thom Yorke: “I am pulling all my work from supermarkets until they pay what we say it’s worth”

2) Online Retailers

Tax dodging isn’t a direct consequence of music industry action, but it does effect new music. Thanks to the tax avoided by the likes of Amazon, HMV and Play.com, we lost out on hundreds of millions of pounds worth of tax income. All that money could’ve gone on something like arts funding, which has been cut in some areas of the UK by 100%. So that’s no theatres, no youth centres, no free rehearsal spaces, no music projects being supported by the Government or local councils. Thanks, CUNTS!

These online retailers also compete on price by either not caring about making a profit from music sales (seeing it instead as a point of engagement: hey, everyone loves music!), by being offered insane discounts because of their pure influence over the market, or just thinking that monopolizing a market is the way forward. Amazon decided to focus on CDs, and now they dictate CD prices. iTunes own the digital download market, now Apple controls the pricing of digital downloads just through its pure enormity. Amazon have also started doing it with vinyl too, which spells disaster for stores unless customers keep their bullshit detectors about them. One rule in business: always leave something in it for the other guy.

One quick example, while you’re here (thanks to Phil at Black Cat Records in Taunton for this story)…

Henry Mancini’s ‘Touch of Evil OST’ on Poppydisc LP, only about 200 copies in the UK. Dealer price to shop from Shellshock, the record’s distributor, is £9.95 plus VAT. Amazon price is £10.90 inclusive of VAT. Independent stores have to sell this for £17 to make any sort of decent profit, while Amazon are selling it at a loss of 86p. Why do this? Well they will have ordered none so they will only do this on pre-sale, to kill the physical market and bring more recurring business to their site.

The winners: Online retailers get loads of new customers and sales/passing trade.

The losers: Labels, who receive less money for their product, therefore cutting their budgets while other stores get an unfair deal, stores which would normally be the first retailers to support new talent (Spotting a trend here?). Oh yeah, and you. Because those robot-operated warehouses in Guernsey employ hundreds less staff than the shops would if those shops still existed on the high street, which they don’t, because everyone buys everything off Amazon.

The next tweet I’d like to see from Thom Yorke: “I am pulling all my work from online retailers who can’t prove they pay full tax in countries they operate in and sell my product for a fair rate.”

3) Professional ticket touting as supported by promoters.

This is the one I totally can’t understand, or really don’t want to. How did it ever get to this? The industry knows the fall-out from essentially turning parts of itself into a racket, just ask anyone involved in radio promotions in the US during the 70s and 80s.

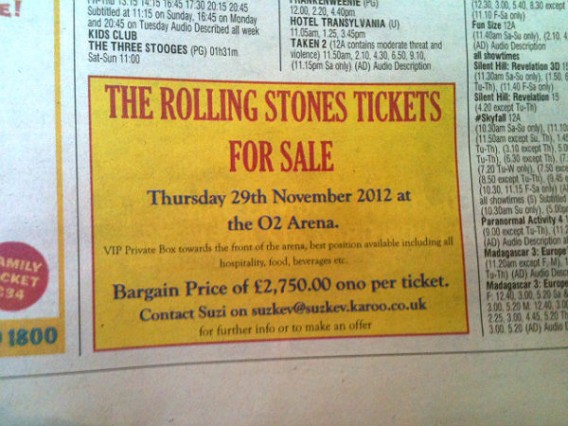

Last February Channel 4 ran a documentary called ‘The Great Ticket Scandal’ and exposed tickets for big arena shows being sold direct from the promoters to secondary ticket sites such as Viagogo and Seat Wave. Did that stop this happening again? Did it hell. This summer’s Rolling Stones Hyde Park tickets turned up on Viagogo just minutes after the event selling out on official ticket retailers, with a starting price of £1,097 each.

Either ticket sellers need to work out a lottery system for purchasing, or they need to impose maximum ticket orders or run resale tickets back through the official retailers in a Glastonbury-esque manner. Anything but ripping fans off with insane ticket prices just because you know they’ve got the money.

The winners: Promoters, people that run secondary ticket sites, and potentially bands who are paid more than their actual worth due to promoters’ knowledge that they’ll be able to inflate prices through the fake second-hand market.

The losers: You, again, whose already squeezed budget these massive holiday funds are going to be made from. Smaller bands who don’t see crowds at local venues anymore because, well, the locals have already spent £150 to see The Stone Roses play a massive field and haven’t got time or money to come and support you.

The next tweet I’d like to see from Thom Yorke: “I am not playing again unless we work out a way to totally wipe away the tout and secondary ticket market from our shows.”

There are people making a lot of money from Spotify, but that’s due to people investing lots of money in tech companies, the rich person’s equivalent to taking the dog for a walk. There are obviously issues with the service, but at least it’s catered to opening massive music libraries to a wide and skint audience. If you want to support new artists, future artists, and essentially any artists currently struggling to make a living, you might want to also focus on industry tendencies that fuck the artist and the customer over. Because at the moment the customer is quite liking this whole streaming malarky, but they won’t like the rest of it.

Physical product is either seen as old fashioned, overly expensive, or a niche treat for the connoisseur. And most of the above points are about the need to support and continue physical product. The reasons physical product is so important (in my humble opinion) are thus:

1) Physical product sounds better, especially vinyl. People scoff at this like production doesn’t matter, but if you went to the cinema and the screen was a bit fuzzy you’d complain and ask for a refund. Digital download formats might get as good as CDs, but it’s unlikely your laptop or iPod will have the same amplification power as an actual CD player. I use a little portable CD player I got about seven years ago to listen to CD promos when I get home. It’s not particularly loud but man it sounds a lot better than hearing them in condensed form through my laptop.

2) Physical product gives you a sense of ownership. Ownership is important, and people care about owning things; if they didn’t they’d stop buying more than one pair of shoes. Music in and of itself doesn’t have a monetary value, it’s simply a piece of music. It’s the transformation from a reel of tape or Pro Tools session to a designed CD package or 12” which gives it its place on your shelf.

3) Physical product gives you a sense of ritual (and friends). I didn’t grow up in London, I grew up in Taunton, where nothing happens, ever. There were no venues, nowhere to ‘hang out’. This is fine when you want to go for a relaxing walk, but when you’re 16, 17 and 18 and itching for something a little bit more exciting than swerving the Daily Mail at the corner shop or the wrestling marines outside the Wetherspoons at Christmas, you’re stuck. Music is how you get on with people in school. It’s one of the first things you talk about on your first day at college. A record store is a place where this can be continued beyond the playground, it’s a place where you can find people with similar interests and talk to people out of your age range in public. It’s also a place where you’ll find loads of new stuff you’ve never heard about before. You’ll spend your spare change from your weekend job in there. I still return to the same shop every time I go home. Essentially, other than first coming across my Dad’s Clash records when I was really young, the record store was probably the second most important ‘event’ in knowing I wanted to work in music with musicians.

4) Physical product keeps more people employed. From the record store owner to the delivery man to the people that press the product in the factory and the distributors needed to sell product to the stores. This might all sound a bit old fashioned, but in a period where jobs are becoming more and more scarce, surely ensuring they still exist is a worthy cause? After all, the current education system seems petrified of teaching us foreign languages or computer coding, so competing with super smart Swedish tech companies is going to be more than a bit of a challenge.

Put that on your Twitter and see if the NME post about it.

by Nicholas Burman

Follow us

Follow us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter Follow us on Google+ Subscribe our newsletter Add us to your feeds