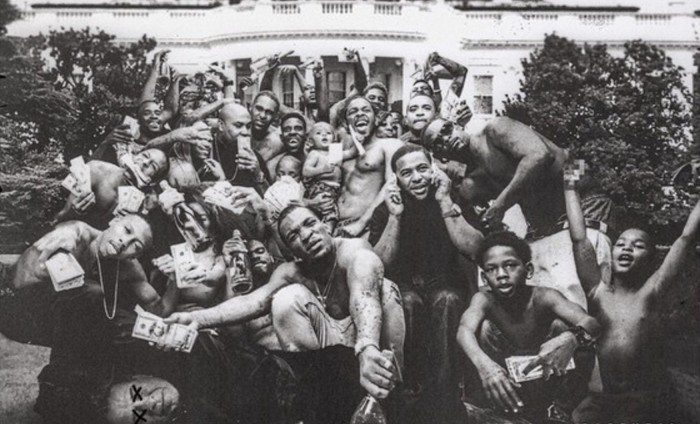

Kendrick Lamar’s third album, To Pimp A Butterfly, commits to an intricate dialogue in which he plumbs the troubled depths of both his personal inner conflict, and a legacy of colonial race issues that bleed through to modern life. The album can be challenging and maybe even overreaches a couple of times, but to dedicate an entire album to this level of depth is a bold move, and only Kendrick Lamar Duckworth (that’s right) could have ever pulled it off.

It’s all set to a challenging sound bed featuring improvised jazz and bare spoken word passages, which demands some degree of listening effort, although this isn’t new territory – Section.80’s ‘Ab-Soul Outro’ features an extended jazz solo supporting a really excellent spoken word/half-rap section, mentioning Uncle Sam and including the line, “I am not the next popstar, I am not the next socially aware rapper.” Kendrick assumes a number of personas, and is joined by legends including Dre, Snoop Dogg, Ronald Isley and yes, 2Pac. The album doesn’t feature the radio-friendly songs that graced previous releases, but when you’re zoning in on equality issues and mapping the dark side of fame this is entirely appropriate. The closest the album comes to a kind of anthem are ‘i’ and ‘Alright’: taken alone these tracks sound upbeat, but in the context of the album they serve as halves of a duplicitous and conflicted inner relationship with money and what it means to be an African-American – particularly the American part.

Section.80 and good kid M.A.A.D city surfaced Kendrick’s consideration of race issues and a message of universal respect, and the campaign continues in this record. The opening track of Section.80, ‘Fuck Your Ethnicity’, is echoed in ‘Complexion (A Zulu Love)’ – “complexion, it don’t mean a thing.” In ‘Momma’, the poem unfolding throughout the album reveals the line “until I go back home” – an answer to Kendrick’s mother’s appeal at the end of good kid – “tell your story to these black and brown kids in Compton” – but home could also refer to Africa, the motherland. In ‘Mortal Man’ Kendrick ponders on what fans would do “if I died in this next line,” and you expect a violent pop-pop-pop to cut him short as it did in the line “if I die before your album drop” in ‘Sing About Me’ – the recurring messages are reinforced and built upon.

But these recurring themes haven’t just resurfaced, they’re also evolving. Kendrick’s butterfly, representing artistic purity, is exploited in pursuit of financial gain; black cultural heritage, the evolution of racism and American political oppression melt into his personal reflection and inner conflict. A bit of a clunky reference to To Kill a Mockingbird, the album picks up where the title falls a little flat, exploring several motifs from the novel: personal growth and understanding; the idea that to understand and empathise with someone you have to “climb into his skin and walk around in it” as Atticus Finch explains to his daughter Scout; the way in which this idea links to current racial inequality; maybe even how Tom Robinson is represented by Finch – that is, by the white man’s moral imperative to protect the vulnerable, in a way cementing a new kind of racial power-play fuelled by altruism. Lamar reflects on all kinds of power, reasserts it, and hands it back to the oppressed, who are oppressed in a much more subtle manner than in the days of slavery – “I freed you from being a slave in your mind,” he says in ‘Mortal Man’.

As well as the themes running through the album as a whole, each song maintains an intricacy and intrigue of its own. ‘Wesley’s Theory’ opens with the line, “Every n**** is a star”, as sung by Boris Gardiner for the blaxploitation film of the same name, but the tone is insincere and plastic, and the repetition of “n****” grates and sounds obscene after the first few listens. If you can keep up with each line being so effortlessly carried off, as is Lamar’s wont, you find every word is meticulously placed and has a meaning, many meanings. Even in the first track, Wesley Snipes’ tax evasion is followed up with a looming Uncle Sam persona, voiced by Thundercat: “We should never gave n****s money / Go back home / Money go back home” which equally means ‘go back home’ and ‘money come back home’, a link to Kendrick’s ideas of home (Africa, Compton, his pre-fame self) and a post-colonial idea of money’s rightful home – white America.

‘These Walls’ opens with what at first sounds like a sensual moan, quickly becoming more disturbing as ominous piano booms and ghostly voices slide in. Your attention is diverted from this plaintive and pain-filled scene with the single word – “sex” – as it’s covered over with smooth funk, but darkness writhes beneath and gives the funky screen an uncanny hue. As well as the walls referenced lyrically, the track is also walled in by the unfolding poem: at the beginning Kendrick says, “I remember you was conflicted…”, repeated at the end of the track, and added to, “…found myself screaming in a hotel room.” The track abruptly ends and male screams begin ‘u’, echoing the female wails of ‘These Walls’. He sings and repeats with James Brown-esque inflections, “Loving you is complicated” (“you” denoting money, fame, the whole game; “loving you” reflecting the unequivocal “i love myself” of ‘i’) until the track yields to a tender melody and broken vocals as Kendrick’s “survivor’s guilt” admonishes him: “You ain’t no brother, you ain’t no disciple, you ain’t no friend – a friend never leave Compton for profit.” The unresolved emotion and lasting guilt drops into ‘Alright’, finding defiant footing: “All my life i has to fight.”

‘i’ begins by channelling an Outkast energy of cheery abandonment, before dissolving into another crowded spoken word section, enacted as if live onstage. It’s an exploration of himself and his memories on a public platform; like the whole album, it’s simultaneously an intense personal exploration and a general public appeal. You can’t tell if the crowds melt away because they’re listening in awe or because Kendrick is slowly becoming more isolated as he tries to appeal to his brothers and redefine the ever-present word: “N-E-G-U-S. Definition: royalty, king royalty.” The “king” links back to ‘King Kunta’, the movie-immortalised slave who repeatedly tried to escape his plantation and eventually had his right foot cut off to prevent him escaping again.

This album can be endlessly interpreted, on every listen it morphs and surfaces new meaning. All I know is, from what Kendrick’s saying, this rich and deeply thought-out album is another evolution of his message and a honing of his unique musical gift: ” … before I’m done with this, y’all gon say, ‘That boy, he did something else that we didn’t think no man could do in music.’”

Amris Kaur

Follow us

Follow us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter Follow us on Google+ Subscribe our newsletter Add us to your feeds